Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Methodology: how I approached the build

- Libraries used (and why these ones)

- How the pieces connect (mental model)

- Performance & trade-offs (the “pain” behind the happy path)

- Follow along in the code (recommended starting points)

- The core idea: map camera landmarks into a physics playground

- Bootstrapping the app: Vite + React entry points

- Getting the webcam feed reliably

- Initializing MediaPipe Hands

- Building the “hands” as physics colliders

- The scene: orthographic camera + Rapier physics

- Touch vs grab: two interaction modes

- Scoring zones: sensors instead of walls

- State, waves, and the “game loop” in React

- UI: make the invisible visible

- The configuration knobs that mattered

- What I’d improve next

- Conclusion

How I wrote a hand tracking game from scratch

Introduction

I wanted to build something that felt like a “real” computer vision project but shipped as a playable web experience: open a page, allow the webcam, and immediately interact with a 3D world using nothing but your hands.

This repository is that experiment: a hand-tracking mini game built with MediaPipe Hands for real-time landmarks, React for UI structure and state, React Three Fiber + Three.js for rendering, and React Three Rapier for physics collisions and sensors.

Play the proof of concept (webcam required): Launch the game

Methodology: how I approached the build

Before writing the first line of gameplay logic, I treated this like a small research project. The goal wasn’t just “detect hands”, it was “make it feel responsive enough to be a game”, and that changes which tradeoffs matter.

My selection criteria looked roughly like this:

- It has to run in the browser with a simple refresh loop (no native install).

- Asset loading and initialization need to be predictable, otherwise the UX dies at the start screen.

- Tracking output has to be easy to turn into something interactive (touching, grabbing, scoring), not just pretty overlays.

- The runtime needs to stay stable under continuous processing (you’re doing CV and 3D every frame).

From there, I picked the smallest set of tools that cover the whole loop: camera input, real-time inference, coordinate mapping, a physics world, and a UI layer that keeps the player oriented.

Libraries used (and why these ones)

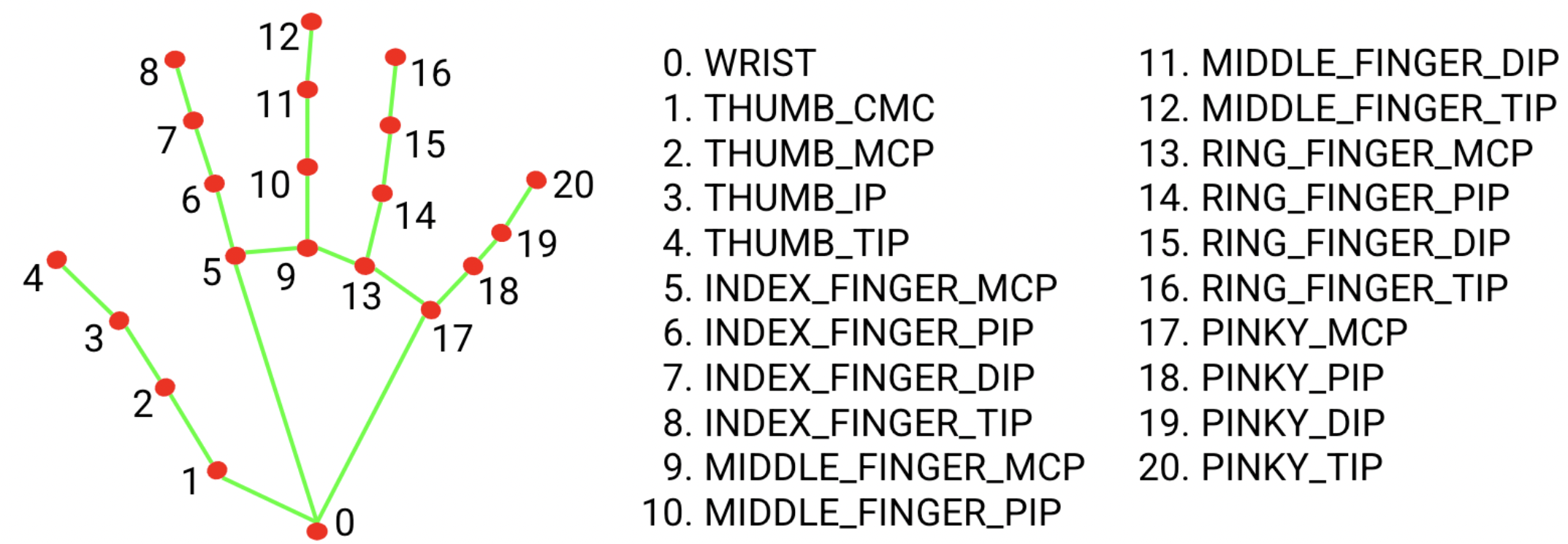

MediaPipe Hands gave me strong tracking quality without having to build or host a model pipeline. The output is also structured (21 landmarks per hand), which is perfect for turning into colliders.

React keeps the app “web-native”: loading states, overlays, and game UI are easy to build and iterate on.

React Three Fiber + Three.js is the bridge between React and a real 3D scene. I can compose the world as components, but still get a proper render loop.

React Three Rapier gives the interactions weight. Instead of faking collisions with distance checks, I can let a physics engine handle contacts and sensors.

How the pieces connect (mental model)

If you’re trying to understand the architecture quickly, this is the data flow I kept in my head while building:

- useWebcam is responsible for getting a video element that is actually ready, plus its real dimensions.

- useHandTracking consumes that video element, runs MediaPipe continuously, and produces HandData[] plus an fps counter.

- Game.tsx composes the system: it passes hands into the 3D world, passes video dimensions everywhere mapping is needed, and decides which overlays to show.

- Scene.tsx turns “hands and objects” into physics reality: colliders, a grab system, touch detection, and scoring sensors.

- useGameState keeps score, waves, lives, and UI events in a way that still feels like React rather than a custom engine.

Performance & trade-offs (the “pain” behind the happy path)

This stack is heavy: MediaPipe inference, a physics step, and a WebGL scene all have to cooperate in real time, and you feel every millisecond of latency.

- Why React for a game? This is a casual, discrete-interaction game. Most state changes happen on events (touch, deliver, miss), not every frame, so React state stays manageable. For a twitch game, I would drive gameplay from the render loop with refs and keep React for UI only.

- Glass-to-glass latency is real. Camera frames arrive late, MediaPipe adds inference latency, and smoothing adds deliberate lag to reduce jitter. I tuned for stability and “touchability”, not perfect 1:1 mirroring.

- Main thread vs Worker. I kept MediaPipe on the main thread for simplicity. On lower-end devices, a production version should move inference into a Worker and decouple rendering from CV.

Most of the tuning ended up being small constants:

- Jitter vs lag: increasing HAND_SMOOTHING_FACTOR makes motion steadier, but your hand collider trails more.

- Pinch stability: the start/end thresholds (PINCH_START_DISTANCE/PINCH_END_DISTANCE) are a simple hysteresis that prevents flicker.

Follow along in the code (recommended starting points)

The Game.tsx component is the orchestrator. It wires up the webcam, the MediaPipe hook, the game state machine, and decides which layers render (video, 3D scene, overlays, UI). You can see the entire “composition root” in one place:

I’m intentionally not inlining the full component here. Most of it is standard React wiring. If you want the full end-to-end “composition root”, start with that file.

The useHandTracking.ts hook is where MediaPipe is configured, initialized, and run on every frame. It also turns MediaPipe’s raw results into the project’s HandData model (plus an fps counter), which is what the rest of the app consumes:

The interesting parts here are the asset loading strategy (locateFile), the continuously-fed frame loop, and the “domain model” conversion step. The repo has the full implementation.

Finally, Scene.tsx is the 3D “wiring” for React Three Fiber + Rapier. It derives an orthographic camera frustum from the webcam aspect ratio, mounts the physics world, then composes the gameplay primitives: hand colliders, falling objects, scoring zones, and the grab system:

Most of the JSX here is boilerplate scene composition. The key idea is that the camera frustum is derived from the actual video aspect ratio, so the world scale matches what you see on screen.

The core idea: map camera landmarks into a physics playground

MediaPipe gives you hand landmarks in normalized video space (values roughly from 0..1, plus a relative depth z). A physics engine wants coordinates in a consistent “world” space.

This project treats the webcam feed like a 2D input surface that drives a 3D scene:

A webcam video is shown as the background, an orthographic 3D scene is rendered on top, hand landmarks become kinematic physics colliders, and falling objects can be touched or grabbed and delivered into scoring zones.

The key translation layer is the coordinate mapper:

src/services/CoordinateMapper/service.ts

It mirrors X (so movement feels natural like a selfie camera), scales to match the current video aspect ratio, and clamps depth to keep interactions stable.

The important part is that it takes normalized landmark coordinates from MediaPipe and produces world coordinates that match the orthographic frustum:

static toWorld(landmark: NormalizedPoint, videoWidth: number, videoHeight: number): WorldPoint {

const nx = Math.max(0, Math.min(1, landmark.x))

const ny = Math.max(0, Math.min(1, landmark.y))

const mirroredX = 1 - nx

const aspect = videoHeight === 0 ? 1 : videoWidth / videoHeight

const frustumHeight = GameConfig.WORLD_HEIGHT

const frustumWidth = frustumHeight * aspect

const worldX = (mirroredX - 0.5) * frustumWidth

const worldY = (0.5 - ny) * frustumHeight

const normalizedDepth = Math.max(-0.5, Math.min(0.5, -landmark.z))

const worldZ = InteractionConfig.INTERACTION_PLANE_Z +

normalizedDepth * InteractionConfig.INTERACTION_DEPTH

return { x: worldX, y: worldY, z: worldZ }

}

Bootstrapping the app: Vite + React entry points

I kept the browser surface area small and predictable: Vite serves index.html, mounts React into #root, and the game takes over.

Entry Points:

- index.html Defines the single #root mount point and loads the Vite entry module.

- src/main.tsx Boots React and renders <App/> into #root.

- src/App.tsx Minimal wrapper that returns <Game/>.

These are intentionally boring. The whole point is that the app starts with a single DOM node, React mounts once, and then everything lives inside <Game/>.

I’m skipping the boilerplate snippets here. If you want to see the full boot sequence, it’s in the three files above.

Managing MediaPipe assets in a Vite build can be surprisingly annoying. I used a small copy script in postinstall/predev/prebuild so the model assets are always available during dev and build:

Getting the webcam feed reliably

The first practical hurdle is not ML—it’s camera initialization and video metadata.

The hook:

does a few important things:

It calls navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia with a reasonable “ideal” resolution, waits for onloadedmetadata so the app knows the real videoWidth and videoHeight, then stores those dimensions because everything downstream (mapping + world scale) depends on them.

Initializing MediaPipe Hands

The heart of hand tracking lives in:

A few design decisions here mattered a lot for a game feel:

It loads assets via CDN using locateFile (so bundling doesn’t get complicated), runs continuous frame processing with requestAnimationFrame, and exposes an FPS counter so performance is visible during play.

The hook turns MediaPipe output into a small domain model (HandData) that’s easy to pass around the app.

You can see the full “lifecycle” in one hook: instantiate Hands, register onResults, initialize, then keep feeding frames from the video element.

I’m omitting the full implementation here because it’s mostly library configuration. The file above is the authoritative reference.

Building the “hands” as physics colliders

A common trap is to treat hand landmarks like UI coordinates. For gameplay, physics collisions are more robust.

This project spawns a set of spheres (only for selected landmarks) and moves them kinematically:

Two small but important touches:

Fingertips have a larger radius (which makes “touching” objects feel less pixel-perfect), and smoothing reduces jitter so the collider doesn’t teleport; it lerps toward the target using src/services/Smoothing/service.ts

HandColliders.tsx is the “spawn colliders from landmarks” bridge. It selects a subset of landmark indices, maps each one into world space, and creates a collider sphere per landmark.

HandColliderSphere.tsx is where the “game feel” starts to show up. It makes fingertips fatter, then uses setNextKinematicTranslation so Rapier treats the hand as a kinematic driver instead of a dynamic body:

const isFingertip = [4, 8, 12, 16, 20].includes(landmarkIndex)

const radius = isFingertip

? VisualConfig.HAND_SPHERE_RADIUS * 1.5

: VisualConfig.HAND_SPHERE_RADIUS

useFrame((_, delta) => {

const next = SmoothingService.lerpPosition(

currentPositionRef.current,

targetPositionRef.current,

InteractionConfig.HAND_SMOOTHING_FACTOR,

delta

)

rigidBodyRef.current.setNextKinematicTranslation({ x: next[0], y: next[1], z: next[2] })

})

This is also where I traded a bit of latency for stability: smoothing reduces jitter, but it means the collider trails behind your real hand slightly.

The scene: orthographic camera + Rapier physics

The 3D world is intentionally “flat” in the sense that an orthographic camera makes interactions feel like dragging stickers on a screen—except it’s still real physics under the hood.

The scene computes a frustum based on the actual video aspect ratio so world coordinates match what you see behind the canvas.

This is the part that keeps the 3D world “locked” to whatever the camera is doing. WORLD_HEIGHT stays constant, while frustumWidth adapts to the webcam feed.

Touch vs grab: two interaction modes

I wanted two distinct actions:

Quick touch means holding your fingertip on an object briefly, while grab & drag means pinching to pick the nearest object within a radius, then moving it.

The grab system:

uses a pinch detector:

src/services/GestureDetector/service.ts

and translates a “cursor” landmark (middle MCP, or midpoint between finger tips) into a world target.

The “pinch” itself is deliberately simple and stable: a two-threshold hysteresis so you don’t flicker between pinching and not pinching every other frame.

const wasPinching = this.pinchStateByHand.get(handIndex) ?? false

const isPinching = wasPinching

? distance <= InteractionConfig.PINCH_END_DISTANCE

: distance <= InteractionConfig.PINCH_START_DISTANCE

Then useGrabSystem turns pinch + cursor into object selection. It maps the cursor into world space, finds the nearest body within GRAB_RADIUS, and stores a per-object grab target:

In other words: pinch creates a “grab intent”, and the system picks the closest candidate inside a radius.

On the object side, the renderer combines:

Actual Rapier collisions (hand spheres collide with objects), a “hold-to-touch” timer, and a kinematic mode for dragging.

All of that logic is in:

src/components/items/ShapeItemRenderer.tsx

ShapeItemRenderer.tsx is where “physics object” becomes “game object”. It has to handle multiple interaction modes: collision touches, hold-to-touch timing, and being dragged by a kinematic hand.

At the collision level, it uses Rapier’s collision callbacks and checks for userData.type === 'hand' on the other body:

I also made touch recognition time-based (instead of frame-based) so it feels consistent across machines with different frame rates.

Scoring zones: sensors instead of walls

The scoring zones are physics sensors that allow objects to pass through them without bouncing off.

When an object intersects a zone, the zone reports objectId and colorIndex, which becomes a scoring event.

The zones are built as a small generated list (left/right per Y position) so the layout can be tuned from config:

And the renderer uses a Rapier sensor body. Instead of bouncing objects away, it listens for intersections and reports deliveries back up to game state.

State, waves, and the “game loop” in React

I kept the “game loop” mostly in React state + effects instead of a monolithic engine.

useGameState manages:

Score, wave progression, lives, combo multipliers, and score popups.

Source:

useGameState.ts is where the “game loop” lives in React terms. Instead of a classic while (running) loop, it’s event-driven: touch events mark objects as eligible, deliveries award points, and waves spawn when the current wave is cleared.

The scoring rules are all centralized in onObjectDelivered, including combo logic and game-over handling:

This is also where the “React for a game” trade-off is most visible: useGameState uses React state, so scoring and wave changes cause re-renders. In this project, that’s acceptable because these updates are event-driven and relatively infrequent compared to the render loop.

The main Game component composes the system and decides what layers render:

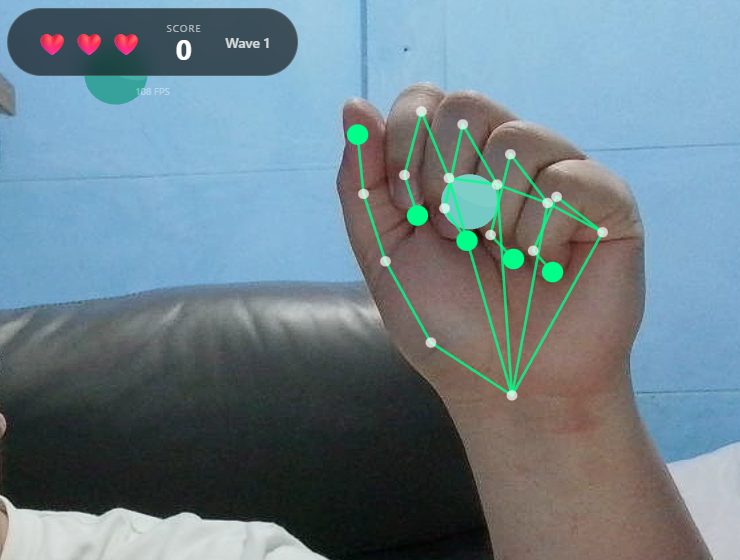

Webcam video layer, 3D scene layer, SVG hand wireframe overlay, and the UI overlay.

The key thing to notice is that it gates the expensive layers behind gameState.isPlaying, and it passes the two pieces of “global context” everywhere: hands and videoDimensions.

I’m omitting the component markup here. The full wiring is in the Game.tsx file linked above.

UI: make the invisible visible

The UI pieces are intentionally simple, but they solve a real usability problem: when tracking is imperfect, players need feedback.

Key components:

These UI components are mostly standard React, so I’ll summarize instead of dumping markup:

- Hand overlay wireframe: src/components/UI/HandWireframe.tsx

- Start screen + loading gate: src/components/UI/StartScreen.tsx

- Score + lives + FPS overlay: src/components/UI/ScoreOverlay.tsx

- Wave announcements: src/components/UI/WaveAnnouncement.tsx

- Score popups: src/components/UI/ScorePopup.tsx

The configuration knobs that mattered

This kind of project lives or dies on small constants. I separated the most “game feel” settings into configs:

Interaction tuning (pinch thresholds, smoothing, grab radius): src/config/interaction.config.ts

World scale + gravity + pacing: src/config/game.config.ts

Colors, sizes, scoring, and combo multipliers: src/config/visual.config.ts

These config files look small, but they are the difference between “it technically works” and “it feels playable”. For example, the pinch thresholds and smoothing factors are all in one place:

Rather than listing constants inline, I keep them centralized in config so I can tune without rewriting logic:

A nice side effect: I can tune the experience without rewriting logic.

What I’d improve next

If I had another iteration, I’d focus on:

- Better temporal filtering (landmark smoothing per joint, not just collider lerp)

- Gesture vocabulary (open palm, swipe, “push” depth)

- Accessibility options (left-handed vs right-handed defaults, colorblind-friendly palettes)

- Mobile performance profiling

But for now, this proof of concept is already a solid foundation for further exploration.

Conclusion

This project taught me that “hand tracking game” is really three separate problems that all have to cooperate:

Perception (MediaPipe landmarks), mapping (turning normalized coordinates into a stable world), and interaction (physics + gestures + feedback).

Once those layers are clean, the game becomes surprisingly straightforward: spawn objects, detect touches and deliveries, and make the UI celebrate what the player just did.

If you want to build your own version, start small: get the webcam + landmarks rendering, then add one physics object, then add one scoring rule. By the time you have those three pieces working together, you’re already most of the way to a playable hand-tracking experience.

Fediverse

Reply to this post on Mastodon

Bluesky

Reply to this post on Bluesky

@richardorilla This is really cool 👍